WASHINGTON FOREST PROTECTION ASSOCIATION

Natural Resources Conservation

Habitat protection is more than just safeguarding the shelter or space that an animal requires to live. It’s about understanding the function and patterns of the ecosystems in which Washington’s fish and wildlife thrive. WFPA’s member companies are using collaboration and science-based research to recognize these life patterns to keep their private forests and the wildlife habitat healthy.

HABITAT PROTECTION TAKES COLLABORATION AMONG FOREST STAKEHOLDERS

Collaboration among forest stakeholders is essential to keeping not only our state’s endangered and threatened species safe, but all fish and wildlife within forest boundaries. Federal and state agencies, county governments, Native American tribes, private forest landowners, and communities all contribute to shaping the forest policies and practices for the state of Washington. The Forests & Fish Law, for instance, is the result of 18 months of study and negotiation involving scientists, regulators, and policy makers representing each of these stakeholders. By working together, fish and wildlife have the needed protection to sustain their vital habitat.

HABITAT PROTECTION TAKES RESPONSIBLE FOREST MANAGEMENT

WFPA member companies practice responsible forest management by using science-based research to protect habitat by understanding how their forest practices impact the environment. From compliance of federal and state laws to building timber harvest plans that minimize environmental impact, private forest landowners are taking the necessary steps in their everyday practices to be stewards for the water, soil, and wildlife of working forests.

NATURAL RESOURCES POLICYMAKING

The Pacific Northwest is one of the world’s major timber producing regions with its regional capacity to produce wood on a sustained yield basis. Washington’s private forest landowners operate in a climate characterized by the public’s dominance and influence over the state’s natural resources. The political system, statutes, tribal treaty rights, and a reliance on cooperative management approaches to natural resources, all invite public involvement into natural resources policymaking. Since human perceptions of forest management practices may have substantial implications for how we manage forests, over the last century, WFPA has developed and evolved as an organization specifically designed to address this unique and complex operating environment. WFPA represents private forest landowners in a multitude of forums and processes; focusing on protecting private landowners’ property rights, ensuring fair taxation, and shaping the political and regulatory system affecting our industry.

In response to Endangered Species Act (ESA) fish listings, Clean Water Act (CWA) impaired streams and tribal treaty obligations, private forest landowners took a pro-active approach to define their environmental responsibilities to protect fish and water and maintain a viable timber industry. The 50-year HCP was based on the Forests & Fish Law, a consensus derived set of protections for fish habitat and water quality designed to meet four goals:

1) To provide compliance with the Endangered Species Act for aquatic and riparian dependent species on non-Federal forestlands”

2) To restore and maintain riparian habitat on non-Federal forestlands to support a harvestable supply of fish;

3) To meet the requirements of the Clean Water Act for water quality on non-Federal forestlands; and

4) To keep the timber industry economically viable in the state of Washington.

The FPHCP defined a baseline of environmental protections in exchange for federal regulatory assurances that forest practices meets the requirements of the ESA and CWA assurances. WFPA’s efforts concentrate on enforcement, defense, and protection of these baseline rights and regulatory assurances. WFPA works to attain the public, political, legal and scientific support necessary to uphold the assurances committed to in the 50-year HCP.

WASHINGTON’S FORESTRY PRACTICES ARE SOME OF THE TOUGHEST IN THE NATION

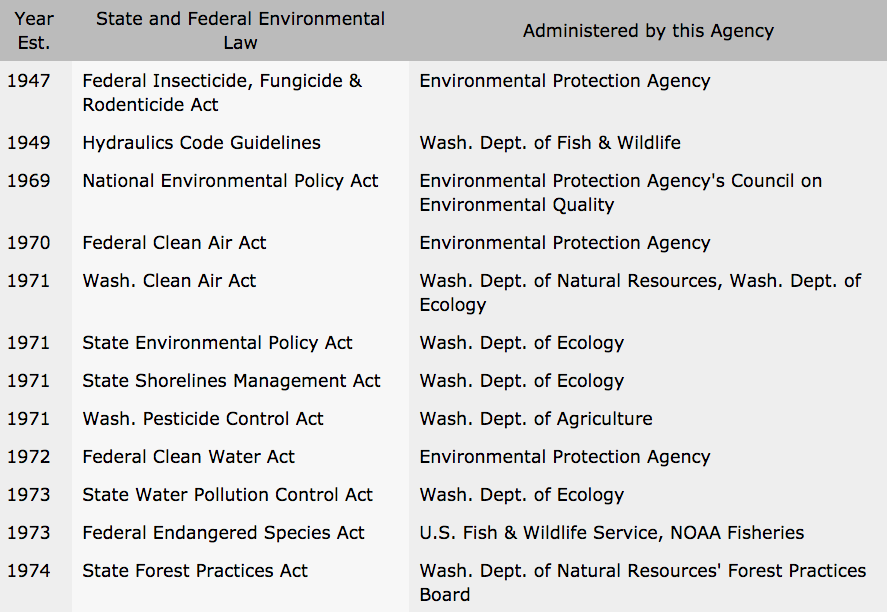

Forestry is regulated by state and federal environmental laws and subject to Native American treaty rights.

Forest management activities in Washington State, including those on privately owned forestland, have been regulated since 1974. That’s when the state first adopted the Forest Practices Act. Forest practices are activities related to growing, harvesting or processing timber and requires a permit. The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is charged with enforcing the Forest Practices Act. These regulations have been strengthened over time. In fact, now they are some of the most stringent in the nation. They are designed to protect public resources, such as fish, water and wildlife, on state and private land, and also ensuring that a new forest is planted after harvest.

- State forest practices rules have been amended and strengthened 13 times since they were established in 1975.

- Washington State has the largest multi-species Habitat Conservation Plan in the country.

Shifting Land Use Policies In The 19th And 20th Centuries Affect Forest Ownership Patterns

During most of the 19th century, it was national policy to transfer federal lands to private use and ownership to encourage the expansion of agriculture and settlement. During this period, more than one billion acres, or over half the land area of the U.S., was transferred from federal to non-federal ownership. The late 19th century marked a shift in Federal land management priorities with the conservation movement concern over the depletion of water, forests, minerals and soils. Policies were enacted to retain rather than dispose of federal lands. The first national parks, forests, monuments and wildlife refuges established, effectively withdrawing these lands from settlement.

The Environmental Movement And Environmental Legislation Challenge The Forest Industry To Restructure

In the 1920s, the three-century-long conversion of United States forests to farmland largely halted due to shift from an agricultural based to industrial based economy. The latter part of the 20th century is marked by a movement into second-growth tree farming, the growth of the environmental movement and the reduction of timber harvest from federal lands, especially in the Pacific Northwest. The 1960s-70s saw landmark environmental legislation passed, with the Clean Air, Clean Water and Endangered Species Acts. Pressure from environmentalists and regulations virtually shut down the national forests to logging in the Pacific Northwest during the early 1990s. After massive layoffs and mill closures during the 1990s, the industry has restructured and is more efficient, producing steady and sustainable lumber output.

WASHINGTON ESTABLISHES MODEL FOR NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Having learned that litigation is not the most productive way to create lasting forest policy solutions; in the mid-1980s private forest landowners entered into a collaborative process with other groups who had a stake in forest resources. This was the beginning of a new way of solving natural resource management issues and resulted in the Timber, Fish & Wildlife Agreement (TFW) of 1987. The legislature amended the Forest Practices Act in February 1987 to incorporate all of the TFW recommendations. TFW has become the model for the way Washington private landowners resolve natural resource issues.

Forest Policy for the 21st Century

Now firmly rooted in state forest environmental policy, the newest changes to forest practices are a result of the collaboratively based Forests & Fish Law, a science-based plan developed over 18 months with county, state, federal, tribal and private landowners and approved by the state legislature in 1999. WFPA members took the lead in bringing together the other stakeholders who developed Forests & Fish. The Department of Natural Resources began implementing the law in 2000 and passed permanent forestry regulations in July 2001. Forests & Fish now protects fish habitat and water quality on more than nine million acres of state and private forest land. Thanks to this ground breaking law cool, clean water in our streams will be maintained by significantly wider forested buffers along streams, and improved road construction and maintenance standards, as well as additional changes in forest management practices.

Private Forest Landowners Go Beyond Timber Industry Regulations

State forest practices rules have been amended and strengthened thirteen times since they were established in 1975. The most recent changes are a result of the Forests & Fish Law, adopted by the Legislature in 1999 in response to federal listings of endangered salmon and impaired water quality in state and private forested streams.

Private forest landowners in Washington State have also undertaken hundreds of voluntary programs beyond those required by law. Most of these voluntary efforts relate to protecting fish and wildlife habitat. Others involve reducing the visual impact of harvest. Voluntary efforts are very important because what is best for the environment in one forested area of the state is not necessarily what is best in another part of the state. Therefore, regulations which are flexible and allow for site-specific solutions are generally best.