WFPA advances policies that keep forests working, mills running, and rural communities strong.

WASHINGTON FOREST PROTECTION ASSOCIATION

Endangered Species

Three bird species have been a top priority for Washington forest landowners for many years. These birds are the Northern Spotted Owl, Bald Eagle, and Marbled Murrelet. Foresters are conducting scientific research, practicing responsible forestry, creating needed legislation, and protecting valuable habitat to provide added protection for these endangered and threatened bird species.

Three bird species have been a top priority for Washington forest landowners for many years. These birds are the Northern Spotted Owl, Bald Eagle, and Marbled Murrelet. Foresters are conducting scientific research, practicing responsible forestry, creating needed legislation, and protecting valuable habitat to provide added protection for these endangered and threatened bird species.

Bald Eagle Population Increases and Removed from Threatened & Endangered Species List

Nearly on the brink of extinction, the bald eagle population is again flourishing in Washington State. The Fish and Wildlife Commission, which sets rules and policies for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), recently amended the Bald Eagle protection rules. The result of the rule change is that state Bald Eagle Management Plans are no longer required unless Bald Eagles are listed as Threatened or Endangered in Washington State. The cooperation of landowners was especially important to the bird’s recovery.

Celebrating the Recovery of a National Symbol

The bald eagle was removed from the list of threatened and endangered species in 2007. First listed as endangered in 1967, the eagle has since made a remarkable comeback. In 1963, there were only 417 nesting pairs in the lower 48 states. Today, this number is closer to 10,000. In Washington, the number increased from 105 pairs in 1980, to 848 pairs today.

Many factors contributed to this population increase, including protection of nesting habitat and a ban on the use of the pesticide DDT. In Washington, where about two-thirds of eagle nests are found on privately owned lands, the cooperation of landowners was especially important to the bird’s recovery.

Marbled Murrelet a Threatened Species in our Coastal Forests

The marbled murrelet is a small seabird that nests in the tall trees of our coastal forests. The marbled murrelet is infrequently observed, and in fact, there have been only just over a dozen recorded sightings of occupied nests in the Pacific Rim countries where the bird is found. In 1992 it was designated a ‘threatened’ species under the Endangered Species Act in California, Oregon and Washington State. Its habitat and behavior place it in jeopardy from three major factors, including oil spills, gill netting, and loss of nesting habitat in coastal old-growth forests. To learn more go to USFWS Marbled murrelet.

ABUNDANT WILDLIFE IN WASHINGTON’S PRIVATE FORESTS

Washington’s wildlife population is flourishing in private forests. Deer, elk, black bears, beavers, and bats: a short list of some of the wildlife that finds their homes in Washington’s private forests. They have also been the target of scientific research over the past 20 years or so by WFPA and its members. The reason for conducting this research has been to find out how modern day forest practices can best sustain animal habitat while growing trees for forest products, as well as to find out how these animals influence tree health in the forest.

Timber Harvesting Helps Create Deer and Elk Habitat

Washington’s deer and elk populations thrive on young successional forests, especially in areas following a wildfire or timber harvest. The opening up of the landscape promotes the growth of low-lying vegetation that these mammals feed on. In addition, scientific studies have shown that deer and elk prefer living near forest edges rather than deep in the forests. Harvesting methods, such as clearcut harvesting, can create these forest edges. An abundance of forage, a result of increased sunlight reaching the forest floor from the timber harvesting, provides deer and elk with needed food.

Black Bears Feed On Young Douglas-Fir Sapwood When Coming Out Of Their Winter Dens

Washington State has approximately 35-50,000 black bears, one of the largest populations in the United States. Black bears usually emerge from hibernation in mid-March when natural foods like berries and insects are limited until the warmer summer months. Until these foods are available, bears resort to grasses, skunk cabbage, mosses, cow parsnip and, to the regret of private foresters, the sugary sapwood of trees.

A single black bear can destroy as many as 70 trees per day. They kill or severely weaken conifers by stripping the bark off the base of the tree and eat the sugary sapwood tissue underneath. This is called “tree girdling.” Tree girdling causes millions of dollars in tree damage each year in Washington alone, and has a large economic impact on forest landowners. To reduce damage, landowners have the option of lethal means to control bear numbers through hunting. A newer and more effective method involves a supplemental feeding program to feed black bears during the spring months when food is scarce.

The Mountain Beaver Presents a Threat to Reforestation in the Western Cascades

The mountain beaver, not related to the well-known stream beaver, is a ground-dwelling rodent. It kills or damages trees on thousands of acres of Pacific Northwest forestlands each year. They can be found in the region of the western Cascades from southern British Columbia to northern California. Mountain beavers have sharp cutting teeth and powerful jaws that can bite through tree branches or sapling trunks. In the months of January through March, their natural food supply is limited so they turn to recently planted conifer seedlings. A single mountain beaver living in a recently planted unit can kill up to 50% of the young seedlings on an acre in only one season. Trapping, although rather difficult, has been the primary method of controlling the mountain beaver population.

FEDERAL SERVICES APPROVE STATEWIDE HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN

THE FIRST OF ITS KIND IN THE NATION

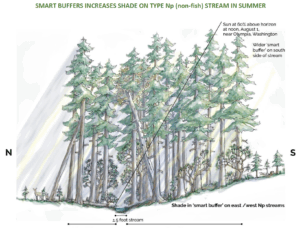

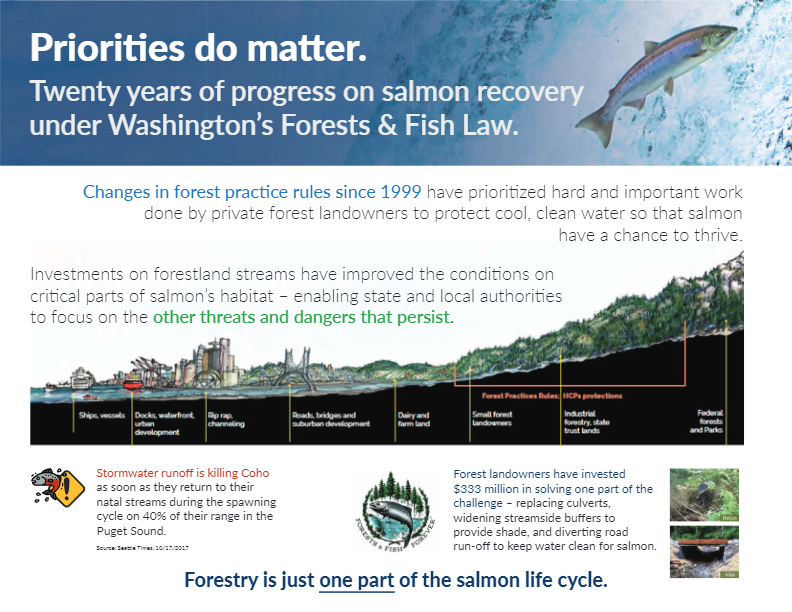

On June 5, 2006, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and NOAA Fisheries did sign the Forest Practices Habitat Conservation Plan. The Forest Practices Habitat Conservation Plan (FPHCP) (also known as the Forests & Fish HCP) is a statewide, programmatic HCP protecting 60,000 miles of streams on 9.3 million acres of forestland, set in motion by the Forests & Fish Law. It ensures landowners that practicing forestry in Washington State meets the requirements for aquatic species designated by the federal Endangered Species Act. The Forests & Fish HCP is one of a kind because of its scope and collaborative development. It is a 50-year agreement with the federal government to increase protection of Washington’s streams and forests. Local, state, federal government, tribes, and forest landowners worked together to develop this plan.

Adaptive management will keep the HCP fresh and current. The plan contains clear resource objectives for the protection of fish habitat and clean water. It also contains a comprehensive scientific research and monitoring program to test to see if resource objectives are being met. If the objectives are not being met, the plan has a defined process to make necessary change to ensure the protection of fish habitat and water quality.

WORKING FORESTS ARE A PREFERRED LAND USE

Private, State, County and Tribal forest landowners have set-aside nearly 2.6 million acres for conservation in streamside buffers for fish and wildlife species representing more than 20% of their working forest. This is due to the tough forest practices laws and requirements Forests & Fish Law, the most comprehensive set of forestry regulations in the nation, endorsed by the federal government through Washingtyon’s 50-year Forest Practices Habitat Conservation Plan.

PROVIDING INCENTIVES FOR CONSERVATION

We all receive enormous benefits from working forestlands. In addition to clean water, clean air, beautiful landscapes, open space, fish and wildlife habitat, and recreational opportunities, working forestlands and a thriving forest products industry provide communities with economic benefits, including good jobs, tax revenues, and environmentally sensitive, locally produced wood products. There are substantial environmental benefits that result from the use of structural wood instead of other less environmentally friendly building materials. These benefits can only be derived if we keep working forests on the landscape. Providing incentives for conservation, or maintaining working forest on the landscape benefits us all.