By Washington Forest Protection Association

Keeping our forests healthy and resilient to wildfire requires a network of dedicated people — including foresters, loggers, truck drivers, biologists, conservationists, mill manufacturers and energy workers who convert forest residuals into biofuels.

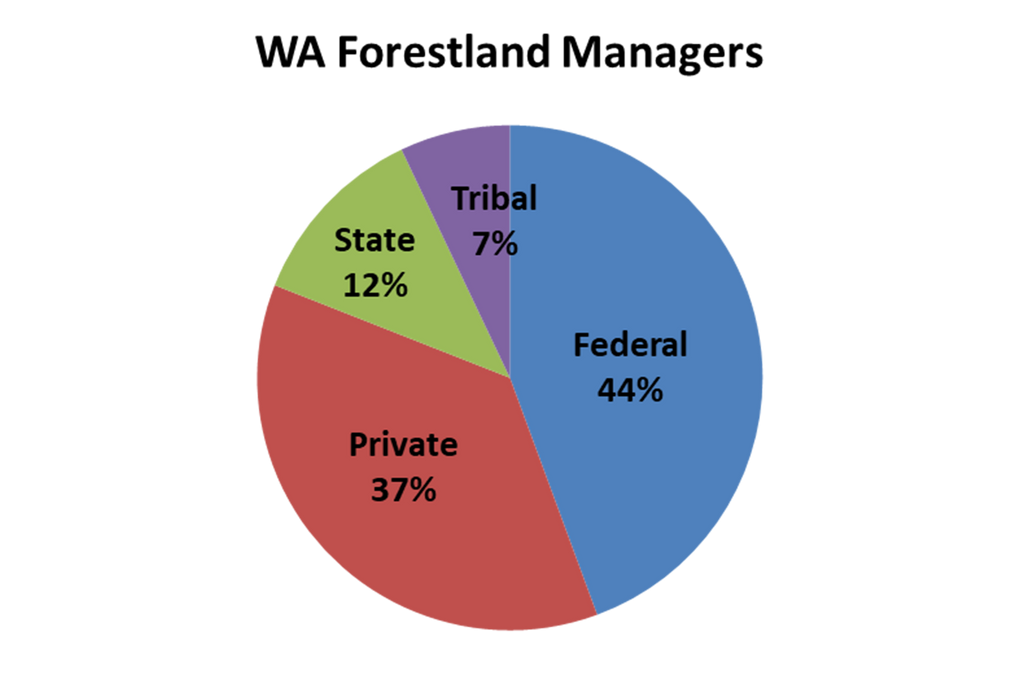

Washington’s diversity of land managers from public, private, state, tribal and federal agencies keep their forests healthy by actively managing the forests to reduce wildfire risk.

The thinning and harvesting from the forest is turned into products we use every day. This network starts with an understanding of the land and what gives forests the resilience to resist catastrophic wildfire. It continues with management of forest land to preserve that balance. And includes creating uses and markets for byproducts of forest restoration efforts.

The land

For Phil Rigdon, who oversees the Yakama Nation Department of Natural Resources, the forest carries sacred meaning; his people have always been connected to the land. “It is the lifeline to our culture,” he says. “Our people go up and practice our way, gathering food and medicine. We gather things the Creator provided for us to use.”

Yakama Nation is an East Cascades forest tribe, with a homeland that sits on 1.4 million acres. This includes a 650,000-acre forest east of Mount Adams. The whole community is involved in taking care of the land, and they have a sawmill that supports everyone as well.

Rigdon thinks it’s important to point out that fire can be good — and doesn’t have to be devastating like we’ve seen with recent catastrophic events. His people have seen fire as an asset to the land versus a cause of destruction, as plants thrive when certain nutrients are released back into the soil. Yakama Nation actively manages their forest and continually attends to its health; they have a Fuels Program that does prescribed burns annually.

Rigdon’s people are Involved in many forest collaborations and talk to local foresters, too. “We engage and share the values that we want,” he says. They’re heavily involved in the network of folks who help look after the land, from state agencies focusing on fish and wildlife to county commissioners, and “all those who care for how our future looks, all those who know we need a different way.”

Fire-resilient forests link past, present and future. One of Rigdon’s favorite places to visit, where he’s gone with elders since he was young, requires a couple-mile hike into the forest. Once arriving at this special spot, he’s surrounded by giant Douglas firs and towering, old cedar trees. He finds great comfort in always “knowing they are there.”

The harvest

Master logger Roger Smith owns RL Smith Logging, a family-owned timber harvesting and trucking company based in Elma. This business is representative of the forest contractors that operate on working forests throughout western Washington, and its team has received advanced training in logging methods that benefit both industry and the forest. Roger and his wife, Carmen, have also been engaged in an “Adopt a High School” program, linking loggers with high school students who may seek a career in the woods. Smith explains that once trees start dying, it doesn’t take more than a year or two before a fire hazard arises. “We reduce wildfire risks by removing diseased, dead and dying trees, as well as snags that pose hazards along roadsides,” he says, “Because many fires are human caused, we also do our part to move flammable material away from the roads, so they don’t ignite.”

On site, Smith and team keep water cannons and fire tools, wagons and equipment (which gets checked weekly). When it’s fire season, they monitor the Department of Natural Resources’ industrial fire precaution level zones. “We have over $3,000 worth of firefighting equipment, so we’re ready to fight fire if something happens,” he says. “Then after we’re done working, there’s a two-hour fire watch to make sure no fire picks up after we’re gone. A logger cares more about a working forest than people can imagine.”

The end products

Vaagen Timbers founder and CEO Russ Vaagen manages and grows the development of mass timber products and services like cross-laminated timber and glue-laminated timber panels, beams and columns.

Vaagen and his team know that a managed forest leads to a healthy forest — one that becomes resilient to wildfire. “If we did not have sawmills, pulp mills, logging contractors, truck drivers and foresters,” he says, “we would have no way to get forest products from the forest to a viable marketplace. That all seems obvious to most, but what most people don’t realize is that technology advances over the last 40 years have made it viable to use small logs/trees to make lumber and plywood.”

This advance means that instead of the majority of forests being clear-cut and replanted, millions of acres are now being thinned and selectively harvested.

“The primary product needs to be healthy, fire-resilient forests, leaving behind the biggest and best trees that are best suited to survive low and medium-intensity fires,” Vaagen says. “The forest products infrastructure will provide a market for the material and jobs for people rural communities.”

In northeast Washington there are two small-diameter sawmills, a plywood mill, two ponderosa pine board mills, an efficient cedar mill, a biomass-to-energy plant and access to byproduct markets that buy wood chips, sawdust and shavings that produce paper, particle board, wood pellets and other agricultural and landscape products. “We have a robust forest restoration program on the Colville National Forest,” Vaagen says. “The state, tribal and private lands are also actively managed. That means many more acres of forest that are thinned to a level where they are resilient to wildfire. This is evidenced by smaller and less frequent fires.”

In north central Washington, there are far fewer acres thinned and restored to health. There is little infrastructure to support the timber industry. Forests remain thick, with lots of small trees and brush surrounding the mature trees that provide some of the best carbon sinks, holding carbon in the forest and keeping it out of the atmosphere. “Unfortunately, these big trees face imminent threat of wildfire that kills the entire forest, choking our collective air with thick smoke for weeks and even months,” Vaagen says.

Vaagen feels optimistic about what is possible. “It will take a great deal of effort and time, but with focus we can have a serious impact on our forests and reduce the harmful smoke and destruction that wildfires leave behind. It’s worth our effort.”

The Washington Forest Protection Association is a trade association representing private forest landowners in Washington state. Members are large and small companies, individuals and families who grow, harvest and regrow trees on about 4 million acres.

Reproduced from the Seattle Times Content Studio